Water Rules

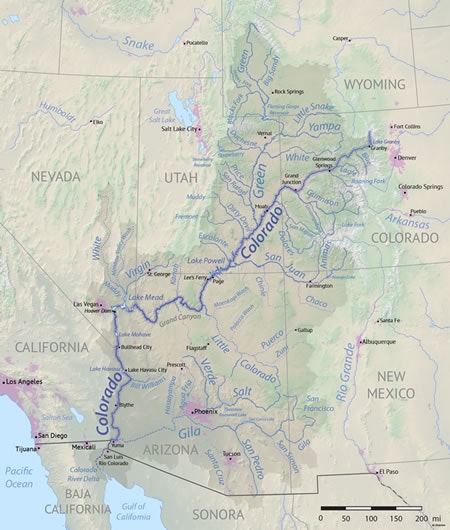

Colorado straddles the Continental Divide, where four great rivers begin: the Platte, the Arkansas, the Rio Grande and the Colorado. Colorado and its neighboring state have argued for more than century over who gets how much water from these rivers. The spirited battle among state began with lawsuits filed in the U.S. Supreme Court in the early 1900’s. Within two decades, efforts to make peace began. The compact clause of the U.S. Constitution became the way states could conclude treaty like agreements to share the most vital of all resources: the public’s water.

Colorado has rights and obligations at the headwaters as the mother of rivers. Nine interstate compact, two Supreme Court equitable apportionment decrees and tow other agreements govern how much water Colorado is entitled to use and consume within its boundaries.

What is a Compact?

A compact is an agreement between two or more states approved by their state legislatures and Congress under the authority of the U.S. Constitution (Article I, 10(2)). Compacts constitute both state and federal law. They are akin to treaties between states with the approval and consent of the federal government. A water compact is a contract between two or more states setting the terms for sharing the waters of an interstate stream.

What is the primary purpose of a water compact?

The primary purpose is to establish under state and federal law how the water of an interstate stream system will be shared between users in different states.

What alternative does a state have to determine its interstate water share?

A state may file a lawsuit in the U.S. Supreme Court asking for an equitable apportionment of interstate stream waters among the states, where the court decides how to fairly divide the waters. Congress can also make an equitable apportionment, as it did by the Boulder Canyon Project Act for Arizona, California, and Nevada’s shares of Colorado River water.

Why would states favor negotiation a compact?

The states can fashion specific enforceable provisions to share the water of an interstate stream. A compact avoids the risk of repeated Supreme Court lawsuits to determine each state’s fair share of the water. Ultimately, it creates certainty for the parties.

What does it mean when a water compact allocation between states refers to “beneficial consumptive use”?

Beneficial consumptive use is the amount of water, typically expressed in acre-feet or by percentage, which each state is entitled to use up entirely within its boundaries from the natural supply available in the river system.

Who can enforce a water compact?

A state can file suit in the Supreme Court for enforcement of its rights under the compact. A state may seek an injunction to require a non-complying state to abide by the provisions of the compact and to provide repayment of water lost to the state and/or monetary compensation. Some compacts establish a commission that has administrative authority.

What is the effect of a compact on water-rights owners within a state?

The state has a duty to regulate water rights within its own state to avoid breaching the rights of another state.

Has the state of Colorado ever had to pay another state for breach of a compact?

Colorado, as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1995 decision, paid Kansas about $34.7 million for breach of the Arkansas River Compact.

Can a state withdraw from or amend a compact?

Compacts typically prohibit unilateral withdrawal by a state and require unanimous consent of all signatory states as well as Congressional consent for any amendment.

What role do federal reservoirs play in compact operation?

Reservoirs constructed, owned and managed by agencies of the U.S. government are often the most important means for administering the provisions of a compact to achieve its purposes and meet its terms.

Do Indian tribal and federal agency reserved water rights have an equitable apportionment or compact water share?

The U.S. Supreme Court held in its 1963 Arizona v. California decision that its equitable apportionment jurisdiction applies only to suits between states and not to Indian tribes. The court held that the reserved rights of the Colorado River tribes are charged against the compact allocations of the states where those reservations exist. Typically, interstate water compacts contain a provision disclaiming any intent to affect tribal water rights.

How do federal environmental laws come into play?

The Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, the National Forest Management Act, and other federal land and environmental laws can impact the construction and operation of federal and non-federal reservoirs as well as direct flow diversions that use a portion of a state’s compact-apportioned water.

Information from Citizen’s Guide to Colorado’s Interstate Compacts

Colorado’s nine Interstate Compacts

Arkansas River Compact of 1948

The compact protects all water uses in existence in 1949 and apportions the benefits of John Martin Reservoir between Colorado and Kansas.

History of the Arkansas River Compact

La Plata River Compact

This compact apportions the waters of the La Plata River between Colorado and New Mexico, by allowing the unrestricted right to use waters by both states between December 1 and February 15 and allocating specific flows and deliveries between February 16 and November 30.

Animas-La Plata Compact

This compact provides agreements that allow for the operation of the Animas-La Plata Project.

History of the Colorado River Basin Compacts

Colorado River Compact and Upper Colorado River Compact (1922):

These compacts allow Colorado to use up to 3.85 million acre feet (MAF), provided the Upper Basin does not cause the flow at Lee Ferry, Ariz., to fall below 75 MAF, based on a 10-year running average (7.5 MAF/year). To learn more, see the Coordinated Long Range Operating Criteria. Learn about Compact Administration in this presentation.

Republican River Compact

Colorado’s consumptive uses are limited to 54,000 AF, plus all uses from Frenchman and Red Willow Creeks.

Rio Grande Compact

The compact establishes Colorado’s obligation to ensure deliveries of water at the New Mexico state line and New Mexico’s obligation to assure deliveries of water at the Elephant Butte Reservoir, with some allowance for credit and debit accounts.

Costilla Creek Compact

The compact establishes uses, allocations and administration of the waters of Costilla Creek in Colorado and New Mexico.

South Platte River Compact

The compact establishes Colorado’s and Nebraska’s rights to use water in Lodgepole Creek and the South Platte River.

The Colorado River Basin covers seven states and parts of Mexico, a drainage area of over 244,000 square miles. Precipitation ranges from 30 to 45 inches in mountainous headwaters areas to less than five inches in desert areas. The historic flows of the Colorado River have varied considerably, both seasonally throughout the year and in dry as opposed to wet periods.

Wide seasonal and yearly fluctuations in Colorado River flows created problems for communities, that depended on Colorado River water for multiple uses, including agriculture,recreation and domestic. In the early 1900’s disastrous Colorado River floods caused significant damage to land and communities in the Lower Colorado Basin. California, Arizona and Nevada, the three Lower Colorado River Basin states, grew more rapidly in population and agricultural use than the four Upper Colorado River Basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico. The decision of the United States Supreme Court in the case of Wyoming v.Colorado established the legal principle that the doctrine of prior appropriation controls regardless of state boundaries. When the other states of the Colorado River Basin realized that rapidly growing California had an opportunity to grab the major share of the flow of the Colorado River, the Upper Basin states were concerned to preserve their fair share of ColoradoRiver water.The Upper Basin States, therefore, opposed new major water development in theLower Basin without assurance of their share of the River.

The water of interstate streams may be allocated by U.S. Supreme Court decree, by federal legislation, or by interstate agreement executed by the affected states and ratified by Congress. After the Wyoming v. Colorado decree, the seven Colorado River Basin states entered into negotiations to better manage the Colorado River, including flood control and water storage, to equitably allocate the Colorado River and to improve water conservation. Delph Carpenter, theColorado member to the Colorado River Commission, was a key exponent of dividing the water of the Colorado River between the two Basins.

The Colorado River Compact, forged by the states and ratified by the U.S. Congress in 1922, is the foundation for the allocation and management of Colorado River water. In the Compact, the water of the Colorado River is divided at Lee Ferry, just below the present site of Glen Canyon Dam. The compact was written so that it would appear that the waters of the Colorado River would be divided on a 50-50 basis between the Upper and Lower basins. Article III(a)apportions 7,500,000 acre-feet (“AF”) of water annually to the Upper Basin and Lower Basin respectively “in perpetuity.” In Article III(b), however, the Lower Basin claims it was “given the right” to increase its consumptive use of water by one million AF annually, which might have been innocuous except for Article III(c) of the Compact concerning future deliveries of water to Mexico. In computing any deficiency in deliveries to Mexico, the Lower Basin has held that its total use is 8,500,000 AF, while the only use accorded to the Upper Basin is 7,500,000 AF, a claim to which Colorado has continuously objected.

Based on an estimate of 17 million acre-feet as the annual flow in the Colorado River, under the Colorado River Compact the Upper Basin must deliver 75 million AF over a ten year period to the Lower Basin states. Given the quantification of the United States* delivery obligation toMexico of 1.5 AF of Colorado River water annually, under the 1944 treaty between Mexico and the United States, and because the average annual Colorado River flow has now been determined to be closer to 13.5 million AF, the Upper Basin’s Colorado River yield is less than an average annual 7.5 million AF. The Mexican Treaty, however, could become the subject of protracted litigation among the Colorado River Basin states. There is unlikely to be any agreement between the Upper and Lower Basins concerning the “deficiency” in deliveries to Mexico as defined in Article III (c) of the Colorado River Compact.

The Colorado River Compact, by its terms, provides that it is not effective until approved by the legislatures of each of the signatory states. After the execution of the Compact, California renewed its battle to obtain Congressional authorization for the construction of the Boulder Dam project. The refusal of the Arizona legislature to ratify the Compact, despite the urging of itscommissioner, was solved by the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 (“BCP Act”), which specified that the Compact would become effective when ratified by the legislatures of six states.To placate Arizona, the BCP Act provided that the Compact would not become effective until the California legislature had irrevocably agreed to limit California’s consumptive use of Colorado River water to 4.4 million acre-feet annually.

The BCP Act also authorized the states of Arizona, California and Nevada to enter into an interstate compact to divide the 7.5 million acre-feet of water apportioned annually to the Lower Basin by the Colorado River Compact. Arizona’s refusal to enter into a Lower Basin compact was at least partially laid to rest by the Supreme Court decision in the case of Arizona v.California, and by certain provisions of the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968.

The BCP Act also gave Congressional approval for the four Upper Basin states to negotiate a compact dividing among them the 7.5 million AF apportioned to the Upper Basin by theColorado River Compact. In 1948, the four Upper Basin states agreed in the Upper ColoradoRiver Basin Compact to the allocation of the Upper Basin’s share of the Colorado River water on a percentage basis to enable a consistent method of determining allocation, regardless of the varying wate rsupplies of the River as follows: Wyoming = 14%, Utah = 23%, New Mexico =11.25%, and Colorado = 51.75%. Only about 20% of the Colorado River Basin lies within Colorado, but about 70% of the Colorado River flow originates with this state. As a result of the various compacts and the accurate projections of river flows, approximately 3 million AF of depletions is available to Colorado annually under the “Law of the River.”

As part of the 1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, Colorado agreed to deliver water to New Mexico from the San Juan River and its tributaries. The state of New Mexico is entitled to approximately 700,000 AF per year from the San Juan River. Over 60% of the surface water in New Mexico flows through San Juan County, including the confluence in Farmington, NewMexico, of the Animas and San Juan Rivers. Approximately 465,000 AF of water is utilized annually by New Mexico water users, including the 110,000 AF transferred through the SanJuan/Chama diversions on the Navajo and Rio Blanco in Colorado to the Rio Grande valley.

Authorized by Congress in 1968, the Animas-La Plata Project (“A-LP Project”) would provide water to the Southern Ute Indian and Ute Mountain Ute Tribes in Colorado in settlement of a portion of their reserved water rights claims, and municipalities, industries and agriculture inColorado and New Mexico. Municipal and industrial water for the towns and industries in SanJuan County, New Mexico would total 34,000 AF annually from the A-LP Project.

Understanding Water Rights:

The laws defining water rights and the institutions involved in water resources allocation represent the framework for managing water resources in the United States. Water rights and water allocation programs in the US have largely been the provinces of the states. At this time, there is no national water rights system.

Water rights law and water allocation arrangements reflect differing traditions and conditions across the country. In water resources, the challenge for government is not one of regulation, but of fair and even-handed allocation. When demand exceeds supply, more sophisticated water allocation arrangements are required than when supply is plentiful.

The law of water rights in the US has included two distinct systems: riparian rights in the East and the appropriation doctrine in the West. A more accurate picture presents three systems: 1) riparian rights; 2) regulated riparianism (which lays a system of government permits and regulation by state agencies on top of the traditional court-made riparian doctrine); and 3) the appropriation doctrine. Groundwater policy is often some blend of these options.

All water in Colorado is a resource owned by the public. In creating water righrs, Colorado law distinguishes between waters of the natural stream, which includes surface water and tributary groundwater, and other groundwater, which includes designated groundwater, nontributary groundwater and Denver Basin groundwater.

Riparian Rights:

Riparian rights are the basic rules to allocate water in the eastern US–considered to be roughly east of Kansas City. These policies evolved almost naturally in an environment where water was generally plentiful and excessive government involvement was unwanted.

Under the riparian doctrine, the right to use water from a stream or lake belongs to whoever owns the land on the bank. Every riparian owner is entitled to use water from the stream. This right is defined as the right to enjoy the advantage of a reasonable use of the stream as it flows through the landowner’s property. This right, however, is subject to an equivalent right belonging to other riparian owners.

Two rules govern how much water a riparian owner may use. The older rule held that the landowner must leave the natural flow of the river unchanged. Each riparian owner downstream was entitled to have the water in its natural condition, without other landowners altering the rate of flow or the quantity or quality of the water. The more modern rule of reasonable use is that each riparian owner may use the water, regardless of the natural flow, as long as their use does not cause an unreasonable injury to any other riparian user.

Regulated Riparian:

With time, increasing population and development in the East have increased the problems of water distribution. The proliferation of problems and an increased faith in government regulation have caused most states to overlay the traditional riparian system with new administrative schemes, such as permit systems, for regulating water use. This has been described as regulated riparianism.

The most important feature of regulated riparian statutes is that direct users of water must have a permit from a state administrative agency to use water. Although the standard for granting permits is typically similar to reasonable use, reasonable use may be applied differently from the common law riparian doctrine.

Appropriation System:

The arid climate of the western US is less conducive to the use of the riparian system than that of the wetter eastern US. As early trappers, miners, and settlers migrated west, they encountered a hostile environment. Early explorers referred to the Great Plains as the Great American Desert and not all believed that it could be settled. It was obvious that most of the land would require irrigation. Limiting use of streams to only adjoining landowners was not practical; such an action would drastically curtail the settlement and development of the new lands, because nonriparian lands would be practically useless.

The early miners are credited with finding a solution to the problem. By custom, they all accepted the fact that the first miner who used water from a stream to work a placer claim was protected against latecomers. Soon this custom expanded to include the use of water for all purposes, not just for mining. Finally, as the land was organized into territories and then into states, the custom became law through express recognition by court decisions, constitutional provisions, and state statutes.

The appropriation doctrine envelops several interrelated concepts. The two major concepts are: 1) a water right is a right to the use of the water; the right is acquired by appropriation; and 2) an appropriation is the act of diverting water from its source and applying it to a beneficial use.

Under appropriation doctrine, the oldest rights prevail. The earliest water users have priority over later appropriators during times of water shortage. Another fundamental philosophy expressed in western water law is that public waters must be used for a useful or beneficial purpose. The appropriator can use only the amount of water presently needed, allowing excess water to remain in the stream. Once the water has served its beneficial use, any waste or return flow must be returned to the stream.

In contrast to a riparian right, an appropriation right is independent of land ownership; the right to a certain quantity of water may be acquired by appropriating and applying water to a beneficial use. Often an appropriation right may be limited to a specific time (e.g., day or night, summer or fall, etc.). Appropriation rights are never equal because first-in-time appropriators are guaranteed an ascertainable amount of water. Unlike riparian rights, which are not lost by nonuse, appropriation rights are held only as long as proper beneficial use is continued. Appropriation rights are subject to abandonment.

(the preceding was based on Water Resources Planning AWWA Manual of Water Supply Practices M50 No. 30050)

Background on Colorado Water Rights System:

Under Colorado water law, the right to utilize the waters of the State is based on the priority of a party’s appropriation of a specified amount of water, at a specified location, for specified uses (a “water right”). The essence of a water right is its place in the priority system. Colorado’s “first in time, first in right” or “prior appropriation” doctrine applies to both surface water and groundwater tributary to a surface stream. In times of water shortage, a senior right may place a “call” on a stream to obtain a full supply. The stream will then come under the administration of the Colorado Division of Water Resources. Reservoir seepage that returns to the stream system is available for appropriation, as is any other unappropriated water of the stream, but the reservoir may be repaired to avoid the loss.

Method of Acquiring Water Rights

The Colorado Constitution declares that the right to appropriate the unappropriated water of the state “shall never be denied.”

The first step of an appropriation is an action on the ground, such as a survey, coupled with an existing intent to apply the water to beneficial use. The appropriation date of a water right is the earliest date on which the applicant can demonstrate the initiation of the appropriation: i.e., the coexistence of both an intent to appropriate and an action on the ground manifesting that intent.

The existence of an appropriation is confirmed and the priority of a water right is determined in a proceeding in state Water Court. An application for a water right is made to the Water Court in the appropriate division of the seven water divisions into which Colorado is divided on a stream basin basis. Water court applications must set forth a legal description of the requested diversion, a description of the source of the water, the date of the initiation of the appropriation, the amount of water claimed, and the use of the water. A priority decreed for an application filed in a calendar year is junior to decrees awarded to applications filed in previous calendar years. An exception exists for a federal reserved federal land reservation for which water was impliedly reserved to meet the land reservation’s primary purposes.

Conditional Water Right

Because some projects take a long time to complete, an applicant for a water right who has taken the first steps to appropriate water for beneficial use may obtain a “conditional” water right with a definite priority. In order to maintain a conditional water right, an Applicant must demonstrate to the Water Court reasonable diligence in perfecting the appropriation every six years from the date the decree is awarded. Reasonable diligence is demonstrated by showing continuous efforts and interest in developing the water right. To change the conditional decree to an absolute water right, an Applicant must demonstrate to the Water Court that the water has been put to beneficial use. The water right may then become absolute with the conditionally decreed priority relating back to the originally decreed appropriation date.

Plan of Augmentation – Water Critical Basins

If an established municipal water supply is not physically and economically feasible for a new project, the Project may obtain a junior water supply from wells or through stream diversions without the constant threat of curtailment by senior water rights by “augmenting” or increasing the water supply in the stream through a court-approved plan of augmentation. The amount of augmentation water that will need to be provided and the time during which it will need to be available will depend on the amount of water and the timing of the stream depletions of the development, i.e. diversions less return flows. Upon the filing of the plan of augmentation with the water court, parties who believe their water rights may be injured by the plan may file statements of opposition. Prior to approval of a plan of augmentation, the Water Court must determine that the operation of the water supply under the “plan of augmentation” will not injure the vested water rights of others on the stream to which the supply is tributary.

A plan of augmentation may take a number of forms. A developer could acquire senior water rights, stop the former uses, and transfer this water to the development. In the alternative, a developer may construct a reservoir to store water early in the year when the stream is not on call for release later in the year when the stream is under administration.

Wells

Colorado has both an administrative and a court system for determining the right to produce and utilize groundwater. To have permission to drill a well, an applicant must obtain a well permit from the State Engineer’s Office (“SEO”). The SEO must grant the permit if the well will not injure the vested water rights of others. When a stream system, including tributary groundwater, is designated water critical, the permit will be denied unless the application can demonstrate a source of augmentation water which will avoid such injury. An applicant, however, may drill test wells without an official well permit if the driller follows certain notification procedures.

While the administrative process provides a right to drill and utilize a well, a decree of the court may be necessary to ensure a legal right to utilize groundwater within Colorado’s priority system. In an order of the Water Court decreeing a Plan of Augmentation, the Court can require the SEO to issue the appropriate well permits.

Prior Appropriation System

A legal framework called the prior appropriation system regulates the use of surface water and tributary groundwater connected to streams. Mandated by Colorado’s Constitution for water of the “natural stream,” this system is called a prior appropriation doctrine. Today, the 1969 Water Right Determination and Administration Act contains the primary legal provisions governing the prior appropriation system, along with certain provisions of the 1965 Groundwater Management Act.

Prior

In times of short supply, court-decreed water rights with earlier dates (senior rights) can use water before decreed rights with later dates (junior rights) may use any remaining water. The phrase “first in time, first in right” is a shorthand description of the prior appropriation doctrine.

Appropriation

Appropriation occurs when a public agency, private person or business places available surface or tributary groundwater to a beneficial use according to procedures prescribed by law. The appropriator must have a definite plan to divert, store or otherwise capture, possess, and control water, and must specify the place of diversion or storage, amount of water, type of use, and place of use. Without such a plan, the potential use of the water is considered speculative and is disallowed.

System

The prior appropriation system provides a legal procedure by which water users can obtain a court decree for their water right. This process of court approval is called adjudication. Adjudication of a water right results in a decree that confirms the priority date of the water right, its source of supply, point of diversion or storage, and the amount, type, and place of use. A decree also includes conditions to protect against material injury to other water rights.

There are two basic types of prior appropriation water rights: direct flow and storage rights. The first takes water directly from the stream or aquifer by a ditch or well to its place of use. The second puts water into a reservoir for use. The prior appropriation system also lays out an orderly procedure for state officials to distribute water in accordance with the priority dates and conditions contained in court decrees. The only exceptions to this order of priority occur when an approved replacement water supply plan is in place allowing out-of-priority diversions when there is a statutory exemption from administration, or when water officials declare a futile call.

Beneficial Use

Beneficial use is the basis, measure and limit of a water right. Colorado law broadly defines beneficial use as the lawful appropriation that employs reasonably efficient practices to place water to use. What is reasonable depends on the type of use and how the water is withdrawn and applied. The goal is to avoid water waste so the water resource is available to as many decreed water rights as possible.

Over time, the types of uses considered “beneficial” have increased in response to the changing economic and community values of Colorado’s citizens. Recognized beneficial uses under the prior appropriation doctrine now include, among others:

- Augmentation

- Colorado Water Conservation Board instream flows and natural lake levels

- Commercial

- Domestic

- Dust suppression

- Evaporation from a gravel pit

- Fire protection

- Fish and wildlife culture

- Flood control Industrial

- Irrigation

- Mined land reclamation

- Municipal

- Nature centers

- Oil and gas production

- Power generation

- Recreation on reservoirs

- Recreation in-channel diversions

- Release from storage for boating and fishing

- Snowmaking

- Stock watering

- Water storage

Water Waste and Return Flows

In Colorado, a water right is a special kind of property right know as a usufructary right. Usufructary means having the right to use a resource without actually owning it. Ownership of the water resource always remains in the public under Colorado’s Constitution.

The saying that a water appropriator must “use it or lose it” reflects only one facet of a usufructary right. This means that if you do not need to use all or part of your decreed right, the water goes to those who can use the water beneficially, according to the priority dates specified in their decrees.

Colorado Supreme Court water law decisions state that a water user may not take from the stream any more water than is needed for beneficial use at the time of actual diversion is made, despite the amount allowed on the face of the water right decree. To divert more water than is needed for beneficial use is water waste; water waste cannot be included within the measure of a water right.

What defines need for beneficial use? Need is a combination of the amount required to move water to the place where it will be used and the amount required by the actual use. For example, agricultural water use can be 20 to 85 percent consumptive, depending on soil type, crop type, irrigation management, geographic location, or irrigation method. Municipal use varies from 5 percent consumptive during the winter to 50 percent consumptive during summer landscape irrigation.

Beneficial consumptive use over a representative historical time period is typically the measure and limit of a water right. It is typically calculated in number of acre-feet of water consumed monthly by the water use and is determined when a water right is proposed for change to another type of use, point of diversion or place of use.

Many types of water use produce ground or surface water return flows. Some examples of return flows are water that percolates below the root zone of a crop and into the shallow groundwater, water seeping from unlined earthen ditches, or discharges from wastewater treatment plants. Return flows are important for satisfying downstream water rights, providing instream flows and delivering water for interstate compacts and equitable apportionment decrees.

Many water rights depend on surface and subsurface return flows. Under Colorado case law, return flows are not wasted or abandoned water. Junior water users cannot intercept return flows upon which senior water rights depend unless they replace them with another water supply of suitable quantity and quality to satisfy senior rights. In contrast, water imported into a river basin from an unconnected source can be used and reused to extinction.

Overappropriation

A watershed, stream segment or aquifer is considered overappropriated if there is not enough water available to fill new appropriations without causing material injury to existing water rights. Water availability is determined by physical and legal constraints. Physical constraints refer to the natural water supply available from year to year. Legal constraints refer to the amount of water already placed to use by senior water rights within Colorado, further constrained by the amount of water Colorado must allow to flow out of the state to fulfill interstate water compacts or U.S. Supreme Court equitable apportionment decrees.

By the late 1960’s, it became apparent that the South Platte, Rio Grande and Arkansas Rivers within Colorado were reaching overappropriated status. This spurred increased use of groundwater, conservation, reuse of imported water, change of agricultural rights to municipal use, water exchanges and augmentation plans. In addition to conditional and perfected appropriations, provisions of the 1969 Water Right Determination and Administration Act address court approval of water exchanges, changes of water rights, augmentation plans, water management plans and substitute supply plans. These provisions allow junior uses of water, including municipal, environmental, recreational and groundwater uses, to operate even if a basin is overappropriated. Water court decrees for new or changed uses and out-of-priority diversions contain provisions to protect against material injury to other water rights.

Definitions

Return Flow – Water that returns to streams, rivers or aquifers after it has been applied to beneficial use. It may return in the form of surface water or groundwater. Many water rights depend upon return flows for their source of supply.

Developed or Imported Water – Water brought into a stream system from another unconnected source, for example, transbasin water or nontributary well water. This type of water can be reused to extinction or used in augmentation or exchange plans.

Consumptive Use – Water use that permanently withdraws water from its source; water that is no longer available because it has evaporated, been transpired by plants, incorporated into products or crops, consumed by people or livestock or otherwise removed from the immediate water environment.